June 15, 2023— Newly published research illustrates that while 340B hospitals tend to treat patients who are sicker and in greater need of care, they do not prescribe more expensive drugs than non-340B hospitals after those differences are taken into account.

The latest evidence appears in the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Researchers examined Medicare Part D data for fiscal year 2020 to see if physicians in 340B-eligible hospitals were more likely to prescribe more expensive brand-name drugs versus the lower-priced generic products available on the market.

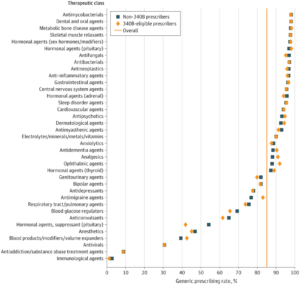

After examining drugs prescribed for patients of 340B-eligible hospital providers versus those ordered by non-340B hospital prescribers, the researchers report they “found no meaningful difference in overall generic prescribing rates.” In FY 2020, generic drugs made up 86.6% of Medicare Part D prescriptions from non-340B hospital prescribers and 86.4% of Part D prescriptions from 340B-eligible hospital prescribers. But after adjusting for differences in therapeutic class mix, the figure for 340B-eligible hospital providers was 86.6% – identical to the non-340B hospital rate.

The researchers looked more closely at the various classes of drugs covered by Medicare Part D and found 11 classes for which 340B-eligible prescribers had statistically significant higher generic prescribing rates and 17 classes where non-340B prescribers had statistically significant higher generic prescribing rates. In three-quarters of those cases, the differences were less than two percentage points. The researchers concluded that such variation was more evident for drug classes that are not prescribed as much, for which a difference in numbers of prescriptions translates into larger percentage-point differences. For cardiovascular agents, the drug class with the highest use, 340B-eligible prescribers had a 95.9% generic prescribing rate compared to 95.7% for non-340B prescribers.

Important Data for Policymakers

This new research is critically important as policymakers on Capitol Hill debate proposals to restrict the size of 340B. One of the arguments frequently put forward in favor of such legislation is that 340B hospitals have a financial incentive to prescribe branded drugs when a less expensive generic product is available.

Under the 340B statute, eligible covered entities can purchase outpatient drugs at a discount and use the savings to “stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.” 340B requires a minimum discount of 23.1% for outpatient brand-name drugs and 13% for generic products. Some have suggested that the higher savings for branded versus generic drugs could induce 340B hospital prescribers to favor the costlier products.

An important factor in comparing 340B and non-340B hospitals is the type of patients treated by each. For example, the JAMA researchers noted 340B-eligible patients with Medicare are more likely to be dual eligible and/or disabled. Most dually eligible patients qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid because they are living with low incomes. Disabled people who are eligible for Medicare tend to be younger than the traditional group of beneficiaries who are ages 65 or older. Those differences in types of patients also are associated with differences in their health needs and the complexity of their care.

A Growing Body of Evidence

In January 2020, the independent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) issued another important report investigating these factors. MedPAC looked at the use of oncology drugs for Medicare Part B patients diagnosed with five forms of cancer (breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and leukemia and lymphoma). They found that while there were variations in spending by 340B and non-340B hospital prescribers, they were “unable to attribute these findings to incentives created by 340B discounts.” Another study also published in JAMA confirmed that there is no drug spending difference between 340B and non-340B hospitals once beneficiary-level risk factors and hospital characteristics are taken into account.

Like the new JAMA study, MedPAC’s researchers noted important differences in patient mix and hospital size. For example, they noted that 340B hospitals are more likely to be larger teaching hospitals and caring for patients who are young, disabled, and receiving assistance designated for low-income Medicare beneficiaries.

Together, these three reports are part of a growing body of evidence for policymakers to consider as they debate proposals to change 340B.